American Fiction Aims to Redefine Black Culture

Every year, the U.S. observes Black History Month in February, taking the time and space to honor the achievements and stories of African Americans throughout the nation’s history. Originally known as “Negro History Week,” this national observance seeks to teach and celebrate Black history and culture.

The tradition continues today. Since 1928, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), founded by the “father of Black history” himself, Carter G. Woodson, assigns a new theme to help focus the public’s attention.

This year’s theme: African Americans and the Arts. Art, from film to literature, is a tried-and-true outlet for preserving, disseminating, expressing, and defining Black culture.

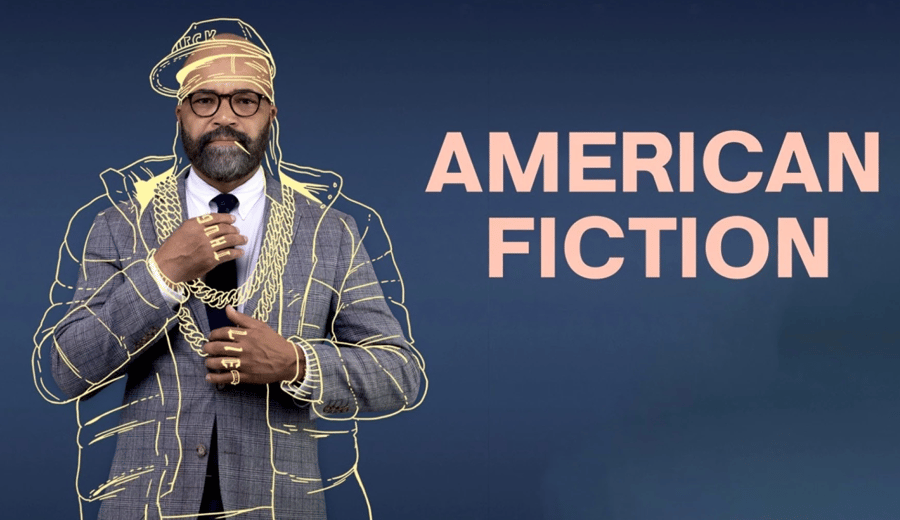

MGM Studios’ American Fiction, currently nominated for 5 Oscars/Academy Awards, including the coveted “Best Picture” and “Best Adapted Screenplay” awards, perfectly encapsulates this theme through a clever literary lens.

“That’s Black, right?”

Social commentary has never been funnier — or touching. Thanks to tasteful couplings of drama, humor, and the Black experience, critics alike praise American Fiction for not taking itself too seriously in its efforts to subvert (and call out) audiences’ perception of “Black culture” through tasteful satire.

Adapted from Percival Everatt’s 2001 novel, “Erasure,” American Fiction centers on out-of-touch novelist and academic, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jefferson Wright), who is frustrated with the publishing world’s obsession with “Black” stories built on overdone tropes.

As his books collect dust (ironically in the African American Studies section of Barnes & Noble) and manuscripts are rejected for not being “black enough”, some others see great success by pandering to stereotypes, like Sintara Golden’s (Issa Rae)”We’s Lives in Da Ghetto”.

To prove a point, Monk decides to craft his own outlandish “Black” tale under a pseudonym, filled with absentee fathers, drugs, crime, and guns. This endeavor quickly spirals into a sought-after bestseller, complete with a movie deal. Monk’s agent Arthur (John Ortiz) later remarks that the novel is “the most lucrative joke [he’s] ever told.”

T-Street Productions and MRC Films produced and financed American Fiction, with distribution rights going to MGM’s Orion Pictures. Cord Jefferson adapted and directed, as well as produced with Ben LeClair, Nikos Karamigios, and Jermaine Johnson.

Monk’s attempt to create a “ghetto” novel that will surely stop editors in their tracks, and get them to rethink their singular view of African American narratives, actually serves as a mirror of the author’s own disillusionment and elitist views of the culture.

Bringing Monk down to Earth

At face value, American Fiction’s withering critique of the publishing establishment’s exploitation of Black creatives and stories to illicit white guilt — and turn a profit — feels devoid of heart-warming humanity at times, as Monk lacks any motivation beyond proving that he’s right and the rest of us are wrong.

The magic of the film shines through as soon as Monk’s offbeat, yet high-achieving family is on screen.

Alongside physician sister Dr. Lisa Ellison (Tracee Ellis Ross) and plastic surgeon brother Dr. Cliff Ellison (Sterling K. Brown), Monk comes from a privileged upbringing in Boston. He is also the favorite child of their mother, Agnes (Leslie Uggams).

While on temporary leave from his university for essentially being an academic snob, he returns to his grand childhood home, which is lovingly maintained by Lorraine the housekeeper (Myra Lucretia Taylor).

As British Vogue’s Radhika Seth points out, the film’s arrival at Monk’s family home reveals just how out of touch with “Black” culture Monk is … at least the culture that his publishers are looking for. He has never faced the “harsher realities of being Black in America” that he later jokingly (or so he thinks) perpetuates in his satirical novel “My Pafology”. Even his loathing for Sintara’s crowd-pleasing novel is rooted in “some intellectual snobbery.”

When tragedy strikes in his family, the monetary need to support his loved ones forces Monk to fall down the same trope-filled rabbit hole as Sintara, though he remains quite self-righteous.

In one pivotal scene, the two authors discuss Monk’s distaste for “We’s Lives in Da Ghetto,” with Sintara trying to pinpoint where his actual distaste may lie. Is Monk mad at the publishing world for diminishing Black stories or simply unable to face his prejudices?

When asked about the scene while speaking with The New York Times, director Cord Jefferson said, “What I really like about that scene is I don’t really know who I agree with, ultimately. They both make interesting points. But I will say that when she says that line, ‘Potential is what people see when they think what’s in front of them isn’t good enough,’ I think it’s the first time we see Monk confronted with the idea that he might be a little self-loathing, that he might have an internal problem with his Blackness. It’s one of the first times that we see him really get clammed up.”

While Cord Jefferson’s feature directorial debut may have been overshadowed at the box office by fellow “Best Picture” contenders Barbie and Killers of the Flower Moon, it has quickly climbed the ranks, humoring audiences and inviting them to reassess their own expectations of “Black” culture.

Add American Fiction to your Black History Month and Oscar film roster immediately.

Topics:

Client Projects

Mariah Flores

Mariah Flores is a journalist and content writer with experience as a News Reporter at LinkedIn News.

Related Posts

Access our blog for the inside scoop on what’s happening around the production office.

Get The Best of The Blog

Get the best of the GreenSlate blog once a month in your inbox by signing up for our GreenSlate Newsletter.

“If you're not using GreenSlate for processing production payroll, then you're not thinking clearly. We run about 10–12 productions a year and have used several of their competitors. I've put off sharing this as I've truly felt they've been a competitive advantage.”

Jeffrey Price

CFO at Swirl Films, LLC